It’s the 15th of December 2023, 2 a.m. in Chennai, the capital of the South Indian state called Tamil Nadu (“Tamil country”) when my plane’s gear kisses the runway tarmac. I haven’t booked a hotel for the night. Instead, I will stay at the airport and take the metro to the city in the morning. The air is crisp, nightly fog reduces the world to a radius of a hundred meters. Under the airport’s giant porch, a stall is selling snacks. “One coffee, please”. The vendor, finishing a discussion with his coworker, answers with this:

Huh, what the hell does that mean? “Do you have coffee or not?” He again wobbles his head, not saying a word. Maybe a language barrier? “Sir, do you understand me?” Head wobble. OK, my last attempt: “Coffee Yes or No?” I support my question with thumbs up and thumbs down. And he replied, in perfect English: “Yes bro of course I have coffee. We just like to confuse foreigners with head wobbling.”

Geez. He got me. India was going to be a ride.

(Only later I learn that this gesture is used to say I’m listening, OK, good, I understand, depending on the context. But done unenthusiastically, it can also serve as a polite No…)

The next few days are spent slowly getting used to India. It is an extreme country in many ways, and it doesn't wait until you’re ready for it. No, India's streets are loud, crowded and bustling, and they take all this madness and just slap it in your face. The honking never stops. Permanently, someone is trying to sell you something or to aggressively lure you into their shop, "special price my friend" (mhm). Mix in chai vendors, beggars, temple or mosque chants, shoeshiners and, because why not, a hole in the sidewalk. Sidewalks are blocked with all kinds of things from motorbikes, construction material, street food vendors to clothing stalls, so it is actually easier to walk on the side of the road.

It takes a few days for me to get used to this level of sensory input. On day 2, I also make friends with the infamous "Delhi Belly" (or should I say "Chennai Belly"), and have the pleasure of spending 36 hours shitting and puking in the hotel bathroom.

Soon after, I head to the train station to buy a ticket for the onward journey. The forecourt is humming, black and yellow rickshaws come and go, which hotel you go Sir, you want chai Sir, a policeman is making an effort to organize the traffic. At the counter, ten people are standing tightly together. I assume they are buying a group ticket, and place myself behind them.

But something funny keeps happening. From time to time, someone leaves and new people join. It quickly dawns on me that this is totally not a group of friends. This here is pure individualism. The motto: Push harder than your neighbor. You happen to be short or rather slim? Well, that’s just too bad... Whenever someone gets their ticket, the scramble intensifies until a new winner is established. After that, there is a nervous calm. For a moment, I am a bit baffled, unsure how to handle this, but I guess my ticket won’t happen on its own. Time to position my body and use it to prevent the people behind me from overtaking.

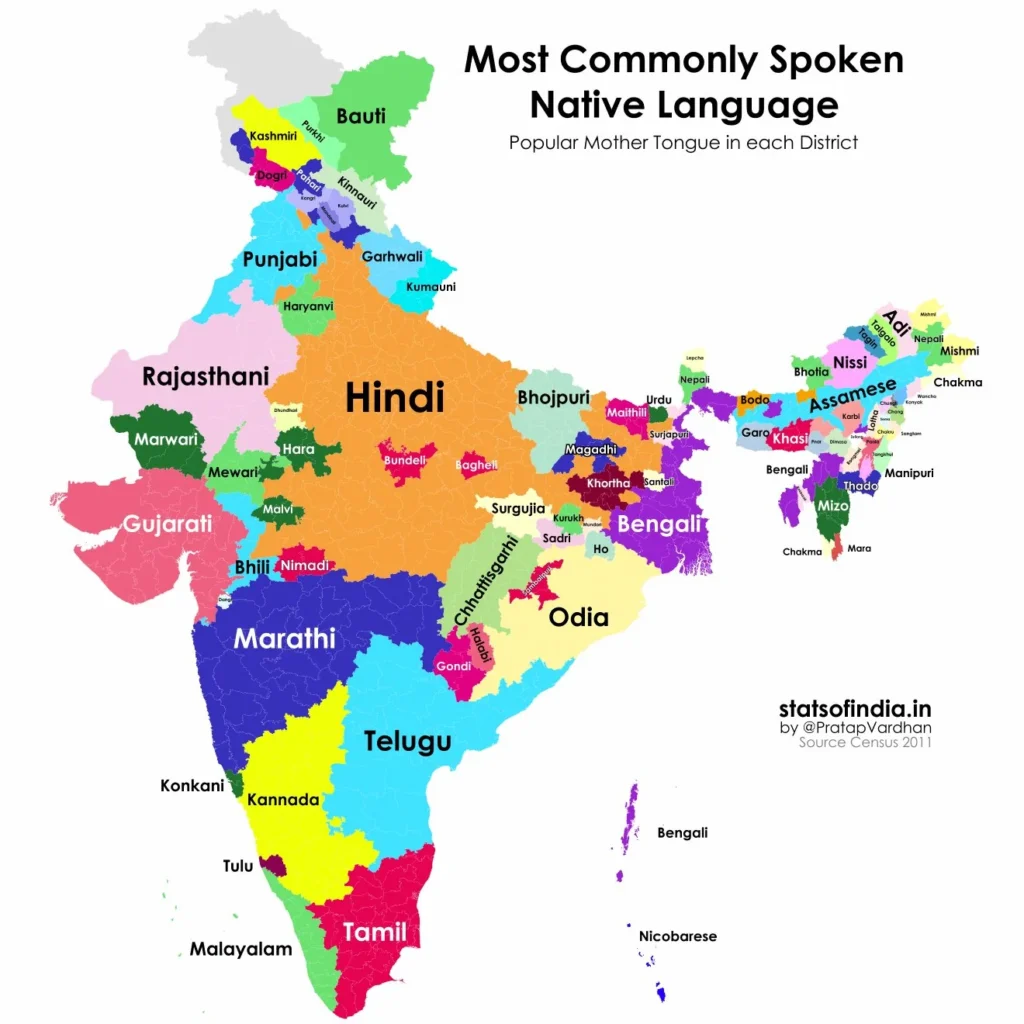

So India needs flexibility (if something goes wrong) and some backbone (for queues, but also, for example, to prevent being ripped off by the street vendors and taxi drivers). Anyone who’s got it, or learns it very fast, will be rewarded with a cultural experience unlike any other. A country with 1.4 billion people (it overtook China in 2023), countless religions, hundreds of languages and thousands of monuments of past empires. The different regions of India each have a strong local identity, which is noticeable for example in the food or the (mostly religious) festivals, all of which are colored by local customs. If you imagine India akin to the whole of Europe rather than as one country, the enormous diversity becomes a tad bit more tangible. Look at this:

All of this is accompanied by the openness with which you are received as a western tourist here. I'm probably getting more attention here than in my previous 26 years combined! People hit me up everywhere. Where are you from? What’s your good name? Are you married? Are you Christian? Are you from USA? Can I take a picture with you? Me too? Me too brother? I also want! It’s relentless. And sometimes if I start telling a story, ten people are listening in the end. It is intense, but I’m not gonna pretend that I don’t like the attention.

In the next town, the South Indian IT hub Bangalore, I encounter Phoebe, Lyman and Teagan from the US in an amazing hostel. We all get on with each other right away and decide to spend New Year together in Goa.

As we exit the train station there, we are – as always – immediately surrounded by a swarm of rickshaw drivers who stubbornly ignore even the third no. It’s impossible to have any kind of group discussion under these circumstances, but we have to decide where we want to go exactly. We walk away from the exit, sit down on a run-down bench by the side of the road and review our options.

Goa promised euphoria, and it delivers. It’s a party vacation hub where, in typical Indian fashion, everything leans towards the excessive side of things. There are not four or five beach bars ("shacks") in front of your hostel, but fifty. When people drink one beer, they drink ten. Not two stalls aggressively tout parasailing, but twenty. Two beaches in particular, Baga and Anjuna, never sleep; on other beaches there do exist quieter corners where you can enjoy a New York Sour under a wonderful bamboo porch and listen to the waves. But anyone who knows me probably also knows that I would only hang out there on a Sunday anyway. Otherwise, I love to dive right into the hustle.

Every morning, I go brunching with Phoebe, Lyman and Teagan next to the beach, then we swim and read in peace, later we climb one of the many hills nearby or enjoy the sunset with a beer on the terrace of the Slow Tide Café. I also get to know Arif and Ikbal, who know each other from Delhi but now live in different places, and Ishan from Hyderabad. All three are open, warm people whom I hope to see again. It is a wonderful week that feels a bit like time off from traveling (what a totally not-privileged statement!). In the partying masses, I am at ease.

The whole thing culminates at a New Year's Eve rave in Shiva Valley, the legendary Goa trance shack at the end of the beach. The club, basically an oversized bamboo hut, is nestled into the hill. Palm trees line the grounds and the dance floor is a sandy area that opens to the beach. Rocks, jutting out into the sea like a tongue, close off the beach. Has there ever been a better setting for a rave?

After a night where raving, constantly drinking water, getting noodle soup on the beach and taking a break on the rocks mix into one memory, the sky develops pink edges and the sun soon rises. Shiva Valley is totally packed yet, it would slowly empty out only in an hour or two. At 8:30 am, Ishan and I call it a night. Bathed in sweat and hormones, we walk home along the beach, waves breaking, birds chirping. What a spec-ta-cu-lar morning. The hammocks in the hostel courtyard are empty and we wind down a little. A warm sun shines through the palm trees and welcomes us in the new year. Peace.

The journey continues to Rajasthan, a state in the dry northwest of India. While Udaipur, Jodhpur and especially Jaisalmer are places that I strongly recommend visiting, I will skip the travel report to tell a story from Jaipur.

My train screeches to a stop in Jaipur Junction and once more, I instantly fend off a group of autorickshaw drivers. "Which hotel?" "No hotel, train to Agra". I buy a samosa, sit down on a bench and wait for my connecting train to Agra. Another driver (he later introduces himself as Lucky) walks towards me and I mentally prepare myself. "Sorry, I have to go to Agra. In four hours." "No problem" - accompanied by head wobble - "I show you around. The express Jaipur tour. For 250 rupees." A good idea, I’m in!

An hour later, Lucky's friend Juber, also a rickshaw driver, joins us "to do timepass. By the way, do you want to see our home?” Hmm, is that a good idea? The events of San Francisco are flashing through my mind. But we find a solution. "I'll send a picture of you and your license plate to a friend." "Yes, and here's my ID card too." "OK, done."

In India, religion is a highly politicized issue, and this is reflected in the living conditions. Mixed neighborhoods alternate with decidedly segregated ones. Juber and Lucky are Muslims in a Muslim neighborhood. The BJP government barely hides its intention to transform India into a Hindu-dominant state. Indian civil society cannot currently effectively counter the right-wing trend.

As we are slowly driving through the residential colony, Juber is constantly greeting someone, I am constantly drawing stares. Juber is something of a volunteer social worker here: When there’s no business, he chitchats with the former construction worker who lost his right foot in an accident. Makes sure that the neighboring kids go to school. Pulls together money for an emergency. He laughs a lot. Grins mischievously as he taps someone on the shoulder from the "wrong" side. "Never forget to have fun." Powerful words from someone who has to fight for customers at the train station day in, day out. That is extremely hard. The income meagre. And yet he still has the energy to care for others. How does he do that?

One key might be a family that keeps giving him strength. We reach their house; it’s one of about a dozen houses placed around a small square. Nine green-yellow rickshaws are parked in one corner. The square features water fountain that is rarely used now that they have piped water here. The houses are solid, but simple buildings - very sparing decoration, no complicated structures, nothing that wastes space or money. Ten family members of all ages live in five rooms. Juber himself is unmarried.

The kitchen is the realm of his mother and sisters; we are served a wonderful Aloo Gobi with Naan. "Our vegetable sellers are eschewed by many Hindus," says Juber. "The electricity bill of everyone here is twice as high as that of our Hindu neighbors." I can’t verify that. What is clear, however, is that the Muslim minority is subject to a lot of discrimination.

Afterwards, we climb to the rooftop. There is a kite festival happening today and tomorrow, and it really takes off after lunch. Fun! Spontaneously I decide to stay in Jaipur a little longer.

The aim is to cut the line of another kite by quickly reeling in your own one. Roof against roof. The whole thing requires quite a bit of skill. Only just before nightfall do I manage to launch the kite autonomously and keep it in the air.

The next day, we are back on the roof, happily cutting lines, when the atmosphere suddenly changes. A moment ago, the scenery of roofs was filled with warm, happy laughter, but more and more aggressive shouts can be heard in between. Lucky and his friends climb down onto the street, and shortly afterwards Juber does too. Not without a warning. "Don't come!"

In the alley leading away from the square, a crowd of a few dozen people has formed, divided into two camps. The more people shove and shout, the less they listen, and soon a free-for-all brawl breaks out. I instinctively hide behind the rooftop wall. Better to be invisible until I know exactly what is going on. From the neighboring rooftop, two people start throwing bricks into the crowd. Screaming, punching, shattering glass. What. The. Hell.

After an eternity, ergo two minutes, the whole thing is over. Shortly before, two piercing voices have been shouting "Stooop, stooop". As Juber & co. trickle in, luckily unharmed, I obviously ask what was going on. "No idea," says one. "Main thing is to be there." Another states that it started as a fight between a few children, in which the families then got involved. "The usual." The usual? The result of the usual is two people in hospital, various bruises and a broken rickshaw windshield. It doesn't sound like a disaster, but it means that three incomes of multiple weeks have been a wiped out. For a rubbish reason. How does that make sense? My two cents: political marginalization, lack of economic prospects, daily competition, no chance of a better future - the frustration is as thick as a Dal Makhani. If it doesn't find another outlet, e.g. in political work, it just erupts in this uncontrolled way.

The two days in Jaipur are the highlight of my trip to India. Sights? I didn’t see a single one. But that doesn't matter. I wouldn’t get to peek into a community like that any time soon. The goodbye at the train station is one of the harder ones.

Lastly, I spend a few days in Delhi. The massive capital of 33 million that attracts people from all over the country. The final boss of all cities, so to speak, because the energy and chaos on the streets here are simply on another level.

And then the moment has actually come.

Something that I couldn't really picture for a long time, it felt so far away.

I've reached the end of the road.

Seven months. Seven countries. Just finished, over, history. It's surreal. Did all of this actually happen?

I'll reflect on that in a next and final post. Here we’ll stick with India.

You are incredible. You reminded me that life doesn't follow a carefully planned straight line - no, it's a dance, between mopeds and rickshaws, in queues and full trains, full of twists and turns. Occasionally your head wobbles. I take a piece of you and keep it with me forever.

India, you have my heart.